BRIEFING NOTE 6 - REMEDIATE

Remediate adverse human rights impacts - the process of repairing and correcting the harm caused

Contents

IIIIIIIII 1 Concept of adverse impact remediation

IIIIIIIII 2 Operational-level grievance mechanisms

IIIIIIIII 3 Development of the grievance mechanism

IIIIIIIII 4 Process for managing human rights grievance

in own operations and those of direct suppliers

IIIIIIIII 5 Communication of the grievance mechanism

IIIIIIIII 6 Considerations about vulnerable groups

IIIIIIIII 7 Challenges and recommendations

IIIIIIIII 8 Checklist

IIIIIIIII 9 Library of Tools

Objective of the briefing note

This section focuses on the steps involved in remediating harm caused directly by the company's own activities and operations or influencing its supply chain to remediate harm caused directly or indirectly

1

|||||||||

Concept of adverse impact remediation

As part of their responsibility to protect against human rights abuses, companies must take appropriate measures to remediate adverse impacts on people affected by the company's own activities and operations, as well as impacts resulting from business relations within their supply chains.

Remediation refers both to the process of providing compensation for a negative impact on human rights and to the actions and results that help neutralize or correct the negative impact.

Remediation actions can take different forms:

Apologies for the company's mistreatment of workers or communities.

Financial compensation for loss of income or reimbursement to a community for harms suffered, or for workers who paid recruitment fees or received irregular wage deductions.

Restitution: Cleaning up chemical residues from chemical spills and restoring the land to its previous condition, or reinstating workers who have been unfairly dismissed.

Punitive sanctions: Fines for those responsible for the harm, or dismissal of harassers.

Rehabilitation: Providing (or paying for) care, therapy, or support for affected workers or communities, or removing underage workers from hazardous activities and offering them free access to education.

Guarantees of non-recurrence and measures to prevent a repetition of the situation that led to the negative impact.

The need to remedy harm is typically associated with the challenges companies face in preventing or mitigating human rights violations or abuses in the company's operations or supply chain. This can occur for various reasons, such as the absence of risk management procedures, the lack of an organizational culture on gender equality, among others.

2

|||||||||

Operational-level grievance mechanisms

There are different ways in which actors impacted by a company's actions or its business relations can access mechanisms to repair harm. One of them is through judicial mechanisms (e.g. courts). However, beyond this, operational-level grievance mechanisms (established by companies, civil society organizations, or sectoral organizations) can be an effective tool in addressing grievances and repairing harm.

The grievance mechanism consists of the process implemented by the company to receive, manage, and remedy grievances. It is the channel through which affected actors (e.g. workers of the company or its service providers and suppliers, surrounding communities, human rights defenders, etc.) can raise irregularities about the direct action or activity of the company or its direct and indirect suppliers.

Companies can establish their own mechanism or participate in a system for managing complaints and grievances that enables proactive management of human rights impacts in their own operations and supply chain. This includes reviewing and updating their own systems and procedures, and engaging with their suppliers so that they, in turn, review and update their system.

Grievance mechanisms play a critical role in fulfilling the responsibility to respect human rights:

supporting repair when a company causes or contributes to negative impacts;

allowing problems to be addressed before they escalate and helping to identify patterns over time for broader human rights due diligence;

allowing the impact to be properly assessed, with the filing of complaints being just one of the steps in the mechanism.

3

|||||||||

Development of the grievance mechanism

The grievance mechanism must cover all the operations and activities of the company and its subcontractors and be available to the actors involved in its supply chain and other interested parties[1].

It is important to clarify the purpose of the mechanism and its target audience, define the minimum conditions necessary for the grievance to be investigated and formalized, inform which are the channels for submitting the complaint and which elements must be included for its consideration.

In addition, the mechanism needs to be able to receive complaints on any human rights issue and be aligned with the United Nations (UN) eight effectiveness criteria[2], reflected in the points below[3]:

The grievance mechanism...

is confidential and anonymous and guarantees non-retaliation against rights-holders. It needs to provide trust and reassurance that the parties involved in the grievance will not be punished

is known and accessible to all potential users and offers appropriate assistance to those who may face specific access barriers

is communicated internally to all levels of the company and externally to all relevant business partners and stakeholders

has sufficient resources for its maintenance and a dedicated team for its management

has a clear and known procedure with indicative deadlines for each stage, types of processes, expected results, and means of monitoring implementation

Rights-holders...

are involved in the development and operation of the system and the resolution of grievances

are not obliged to renounce to any other type of remediation acquired in order to receive compensation/remediation from the company

are informed about public mechanisms for access to remediation

have access to legal support or any other support necessary to guide them through the process and keep them informed of their rights

can report illegal or problematic activities

are kept informed of the progress of the actions and have sufficient information on the performance of the mechanism

All complaints are investigated fairly and equally, including those raised by vulnerable and/or marginalized groups such as migrant workers, women, and indigenous peoples

The channels for registering complaints and the monitoring and analysis processes make use of available technologies

The results and solutions comply with internationally recognized human rights

The process opens up space to identify lessons learned in order to improve the mechanism and avoid future grievances and harm

Dialogue with stakeholders is used as a means of addressing and resolving grievances in order to bring different perspectives to the process so that it adequately represents their demands and needs

[1] A company can choose to have unified or separate grievance mechanisms for complaints and grievances related to its own operations or supply chain.

[2] The effectiveness criteria are as follows and are described in Principle 31 of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Legitimate, Accessible, Predictable, Equitable, Transparent, Human Rights Compliant, Source of Continuous Learning, and Based on Dialogue.

[3] Based on the following publication: Remedying human rights grievances in the supply chain - Proforest

4

|||||||||

[5] The company's direct suppliers refer to companies that supply raw materials (e.g. sugarcane), inputs (e.g. agrochemicals) or services (e.g. labour for maintenance processes)

[6] At a minimum, the timebound action plan should include the following elements: corrective actions to be taken by the supplier; how the harm will be remedied; systemic actions the supplier will take to prevent or mitigate the recurrence of the damage; inclusion of affected parties and other relevant actors (e.g. the complainant and experts on the matter).

Process for managing human rights grievances in own operations and those of direct suppliers

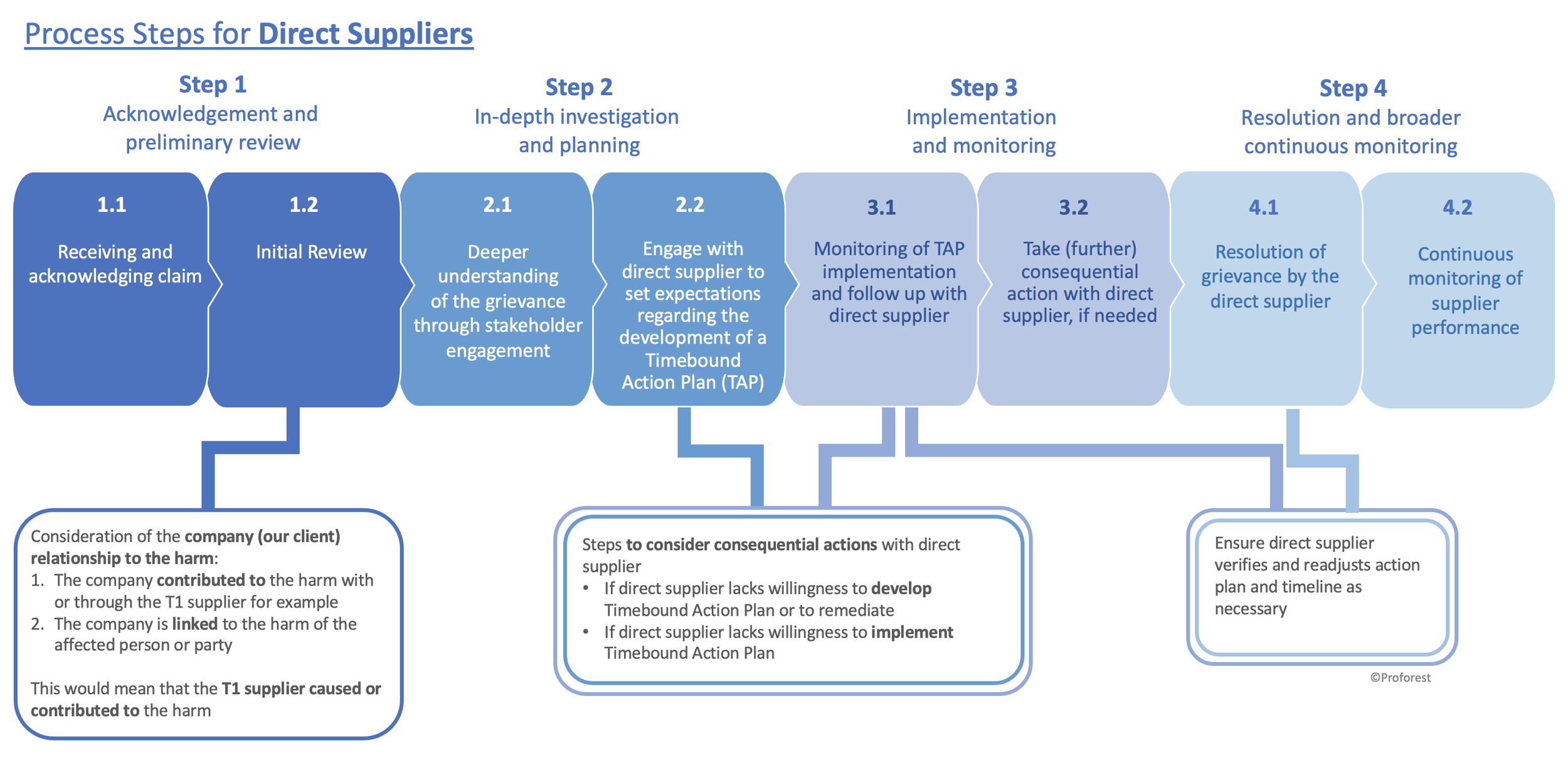

Regardless of whether the grievance raised is about the company's own operations or of its supplier(s), the main stages of a grievance management process are the same (see figure below). The specific actions of each of the steps vary when the grievance is directed at the company's own operations or at its supplier.

The following figures compare these two scenarios (for own operations and direct supplier) and their respective grievance management process.

Step 1. Receiving and registering grievances

When a complaint is received, the first step is to log it in a register and consult the governance structure to check responsibilities, which need to be clearly defined in this document.

The designated individual/group will be responsible for communicating to the complainant[4] (or the direct supplier, if the complaint is made against a direct supplier) the results of the initial assessment; informing them of the next step, which is usually to carry out an in-depth investigation of the complaint (if the initial analysis suggests that this is necessary); and informing them of deadlines.

Step 2. Preliminary assessment

At this stage, the level of priority of the grievance is assessed according to its seriousness (the more serious, the higher the priority) and the company's relationship to the harm (whether it caused, contributed to, or is linked to the harm).

At this stage, when the grievance pertains to the company’s own operations, the company must establish a clear timetable for communicating the results of this initial analysis, the full investigation process, and timelines to the complainant. Ideally, this should be within 5 days to 2 weeks.

Grievances in direct suppliers[5]

It is important to understand the level of the commercial relationship with the supplier, considering its relevance in terms of volumes supplied, the history of the relationship, and how strategic they are. Next, understand the supplier’s relationship with the problem, i.e. whether they are causing, contributing to, or linked to the harm through other suppliers or subcontracted service providers. Finally, it is recommended to contact the supplier to seek an initial understanding of the complaint and its credibility.

Step 3. In-depth investigation of the grievance

An in-depth investigation of the grievance requires a combination of different tools and approaches to gather evidence and gain a better understanding of the root causes of the problem. It is recommended to consult the actors involved and contact the alleged victims (if this does not put them at even greater risk), as well as other stakeholders who would support the company's understanding of the abuse allegations. Investigations provide the necessary basis for action, with the aim of resolving the grievance.

The duration of this stage can vary according to the complexity of the case. However, the company must strive to complete it in the shortest possible time, clearly communicate deadlines to the complainant, and justify delays, if any.

Grievances in direct suppliers

The company needs to understand what its leverage is for each case in question, including the existing relationship with the reported supplier; the importance of the volumes/services the company contracts from the supplier; and the supplier's commitment to developing an action plan to restore and repair the identified harm.

In addition, if the company is linked to the harm (but not contributing), its responsibility is to request information and provide the necessary support to ensure that the investigation is carried out fully and fairly, including all relevant stakeholders. In more complex cases, the company can bring in external experts to support the investigation.

Step 4. Definition of the remediation action plan

This step involves developing a time-bound action plan specifically designed to address the problem raised in the grievance including actions to:

(i) Stop the action, ensuring that the immediate causes of the harm are stopped and that the affected parties are safe. These are called "corrective actions".

(ii) Making changes to the company's processes and systems to prevent the harm from occurring again and outlining mitigation actions. Usually related to the need for systemic changes to address the problem.

(iii) Remedy the harm: in order to restore, as much as possible, the situation prior to the harm and/or compensate for the impact caused.

Grievances in direct suppliers

It is necessary to communicate your expectations to the supplier regarding the minimum elements[6] that the action plan needs to contain (and not necessarily dictate the actions that must be implemented), as well as any other additional expected outcomes.

Also, consider what kind of support the supplier needs to remedy the harm, such as guidance on collaboration with the affected parties, or support (technical, financial, etc.) to make the necessary systemic changes.

If the grievance is related to a systemic supply chain issue, it may be more effective to address the issue through a collaborative approach (e.g. sectoral initiatives or at national/regional level), beyond your supply chain, in order to address the root causes of the issue and prevent its recurrence.

Steps 5 and 6. Implementing and monitoring actions

Implementing the action plan requires:

considering the availability of human and financial resources

allocating roles and responsibilities

defining what results are expected within a certain period of time

establishing mechanisms for monitoring the implementation of the plan, considering the frequency of monitoring and the effectiveness of the actions from the point of view of the affected parties

This stage is fundamental to offering fair compensation or remediation to the affected parties, defined through an agreement between the company and the affected parties. The determination of what constitutes an adequate remediation must include the participation of the affected parties, and the implementation of the actions must be carried out in a way that is satisfactory and safe for these parties.

The company needs to have clear guidance on when a grievance can be considered effectively remedied and communicate its resolution externally.

Grievances in direct suppliers

The company must constantly monitor the development and implementation of the action plan by the supplier and the effective (or not) remediation of the grievance. In some cases, it may be necessary for the company to carry out its own checks, for example by consulting the affected parties or conducting on-site inspections. Monitoring includes checking that the agreed remedy has actually been offered to the victim.

In the case of suppliers unwilling to collaborate in drawing up or implementing an appropriate action plan, consequential measures can be considered, such as reducing the volumes purchased, removing premiums, and suspending the supplier from the supply chain (as a last resort).

Step 7. Grievance resolution

Effective grievance resolution implies that:

The harm caused by the company's own activities or those of its suppliers, or by failures in its management system, has been adequately addressed

There was a correct and in-depth understanding of the harm, based on an independent and impartial investigation

There was input from the affected parties as a source of information for understanding the issue and defining the best course of action

The resolution of the grievance was validated with the affected parties and the complainant. The remediation actions have reached the affected parties, and they are satisfied with the results.

Step 8. Continuous improvement

Finally, the company must continuously evaluate its grievance management process in order to improve it based on lessons learned from previous cases and strengthen its internal systems/processes to prevent or mitigate the occurrence of similar harm. They also need to monitor whether any unintended adverse impacts have arisen from the resolution of the grievance, in order to support the continuous improvement of the systems and processes in place.

In addition, although challenging, it is recommended to monitor the systemic and transformational changes generated from the actions implemented and to maintain an ongoing process of Human Rights Due Diligence.

Grievances in direct suppliers

Once the grievance has been resolved, it is important to continuously monitor the supplier to ensure that the systemic changes implemented are working properly and, if necessary, to review the actions taken.

Monitoring suppliers can take place in various ways. One option is to include the medium and long-term actions set out in the action plan in periodic supplier performance assessment tools. For example, actions aimed at implementing new policies and systems for ethical recruitment and good labour practices, as part of a remediation plan following a grievance of forced labour.

Supporting suppliers to implement grievance mechanisms

Ways in which companies encourage suppliers to establish grievance mechanisms can include:

· Set clear expectations for grievance mechanisms in contracts or codes of conduct;

· Review grievance mechanisms during supplier performance evaluations;

· Build capacity of suppliers on available grievance mechanisms;

· Offer a recourse or appeal mechanism if local grievance mechanisms are inadequate.

Example of a child labour remediation process on sugarcane farms in Belize and lessons learned[7]

In 2014, two 14-year-old children were found working on sugarcane farms without access to education. Although the country's national legislation allows adolescents over the age of 14 to work, the case in question was linked to the FairTrade Certification, which standards prohibits any type of work that interferes with the schooling of children under the age of 15.

The farm in question was suspended from the Belize Sugar Cane Farmers Association (BSCFA) for six months and penalized for not properly inspecting the farms. As a result, the Association suffered a considerable loss in the marketing of its products (because they were linked to a certification), which affected not only the farm in question, but all the other producers, their families, and the economy of the region.

The Association presented a specific due diligence action plan to remedy the damage and prevent its recurrence. This plan included:

developing and publishing a commitment and policy on child labour and child protection;

mapping critical risk points with the community

hiring local youth monitors and training them to carry out awareness-raising, risk assessment, and monitoring actions through household consultations and community awareness-raising

supporting access to remedies in individual cases of child labour

pressuring the government and the Belize Chamber of Commerce and Industry to prioritize a legally binding national child labour monitoring and remediation system.

The Association's approach has promoted an increase in producers' awareness on child labour. The most serious violations are referred to the authorities for repair and, when requested, producer organizations can support the government in remediation.

[4] The complainant may not be directly affected by the action, but nevertheless raises concerns about procedures or management failures that may impact individuals or groups of individuals.

5

|||||||||

Communication of the grievance mechanism

Having an effective process for identifying workers' issues and concerns in a fair and independent manner helps to foster trust and accountability throughout the company. Healthy companies are those that actively strive to uncover issues and encourage all stakeholders to report practices that could be considered risky, unfair or punitive. Ensuring that these mechanisms are accessible and creating a safe environment for all workers, including vulnerable groups of workers, are essential elements in identifying problems and resolving them quickly.

Therefore, socializing the mechanism is a crucial step in this process and implies informing about its forms of use, governance structure, planned steps, and processes for monitoring progress and effectiveness in resolving issues. The target audience can include stakeholders and rights holders, such as workers, local communities, NGOs, customers, suppliers, etc.

For a more effective socialization of the mechanism, consider the following questions:

What should be communicated?

Who is the company and what activity does it carry out?

Who can access the mechanism?

Where, when, and how to file the complaint?

Who in the company is responsible for receiving, registering, and handling complaints?

What are the expectations for the process and response time?

Proper communication brings transparency and credibility to the process as a whole and promotes greater involvement from the relevant actors. Establishing an effective and collaborative communication process that allows workers to report issues safely, anonymously, and without fear of retaliation, and to play a central role in defining actions that impact their quality of life, can help avoid social disruption, work stoppages, labour turnover, and other adverse outcomes for all stakeholders.

6

|||||||||

Considerations about vulnerable groups

Grievance mechanisms, although they are used to raise concerns related to human rights or environmental issues, in some cases are not adequately designed to be accessible to vulnerable or affected groups, or to have procedures that prevent, mitigate, or remedy the negative impacts suffered by these groups. Therefore, it is important that companies have specific policies and procedures for these groups.

In addition, the appropriate type of remediation depends on several factors, including the nature and extent of the impact, national and international laws, regulations, and applicable standards.

For example, take the case of a sugarcane company that uses water from a river to irrigate its plantations, restricting access to water and forcing several communities in the region to travel much further to obtain drinking water. While the men in the communities seek financial compensation from the company, the women may prefer a different form of remediation, as they are the ones responsible for fetching water for their families. For them, a drinking water source closer to their communities would help them the most. This would limit their travel time and the safety risks they run when fetching water.

7

|||||||||

Challenges and recommendations

Initially, it can be very challenging for a company to establish or participate in a grievance mechanism with a remediation process for human rights violations. Victims may even oppose to changes if they are in urgent need of income and have little knowledge of their rights. Some systematic violations, especially the lack of decent or sufficient income, are so widespread that remediation becomes the exception. However, when the company takes control of this process, with transparent, effective mechanisms and a clear commitment to continuous improvement, it is possible to transform remediation into learning for the company.

In addition, in cases of systematic violations, raw material producers should not bear the costs of remediation alone. For example, in West African cane production, the majority of small farmers live in poverty, and child and forced labour and deforestation are prevalent. Data from the Fairtrade Association suggests that for more than 40% of producer groups, the costs of decent child labour monitoring and remediation systems reduce profit margins by 20% [8].

The UN Principles on Business and Human Rights clearly call for sectoral collaboration between actors in the supply chain, allowing for more robust agreements, sharing costs, and improving the minimum acceptable conditions for the production and supply of sugarcane in the country.

[8] Reference: https://www.fairtrade.net/issue/access-to-remedy

8

||||||||||

Checklist

✓ Has the company assessed the need to establish or participate in a grievance mechanism?

✓ The grievance mechanism...

... covers all the operations and activities of the company and its subcontractors?

... is freely accessible to all interested parties?

... follows the UN’s eight effectiveness criteria?

✓ In the process of managing a grievance... ... are the received complaints registered?

... has a preliminary assessment of the complaint been made?

... has an in-depth investigation of the grievance been carried out?

... has a time-bound action plan been defined to address the issue raised? Including stopping the action, making changes to processes and systems, and remediating the harm?

... have remediation actions been implemented, taking into account available resources, responsibilities, and expected results?

... have monitoring mechanisms been established?

... can the grievance be considered resolved?

... is there evidence that the agreed solution actually reached the complainant?

... have the necessary actions for continuous improvement been considered?

... have the specificities of managing grievance at direct suppliers been taken into account?

✓ Have actions been implemented to socialize the grievance mechanism?

✓ Has the company ensured that the grievance mechanism is accessible to vulnerable groups?

9

|||||||||

Library of Tools

In this section, you will find some tools that can help you in the HRDD remediate process.

Guide to grievance management: a series of documents, financed by Cargill and prepared by Proforest, with guidelines on how to deal with grievances in suppliers, with specific documents focused on the following human rights topics: minimum wage, child labour, forced labour, and land rights.

Grievance Channel for Slave Labour and Child Labour:

Ipê System form for registering grievances of work in conditions analogous to slavery and child labour, respectively.

Labour grievance channel: online channel to report labour irregularities.

Guide to grievance management for buyers of agricultural commodities: Developed by Proforest and funded by Wilmar, this guide provides recommendations for buying companies – especially companies at the middle and end of the supply chain – on how to support actions to resolve grievances with direct and indirect suppliers.